Uncovering the Invisible: Analyzing Lubricant Films to Solve the Mysteries of Tribology

Exploring lubrication research behind the oil seals that prevent rotating shaft oil leakage (Part 2)

At NOK, ongoing tribology research focuses on unraveling the mechanisms behind friction, wear, and lubrication to gain precise control over these phenomena. These efforts have contributed to developing products like oil seals, which are designed to contain liquids and gases while allowing components such as rotating shafts and pistons to move without obstruction from friction. In Part 2, we take a closer look at how NOK is observing lubrication states and applying those insights to develop even more advanced mechanisms.

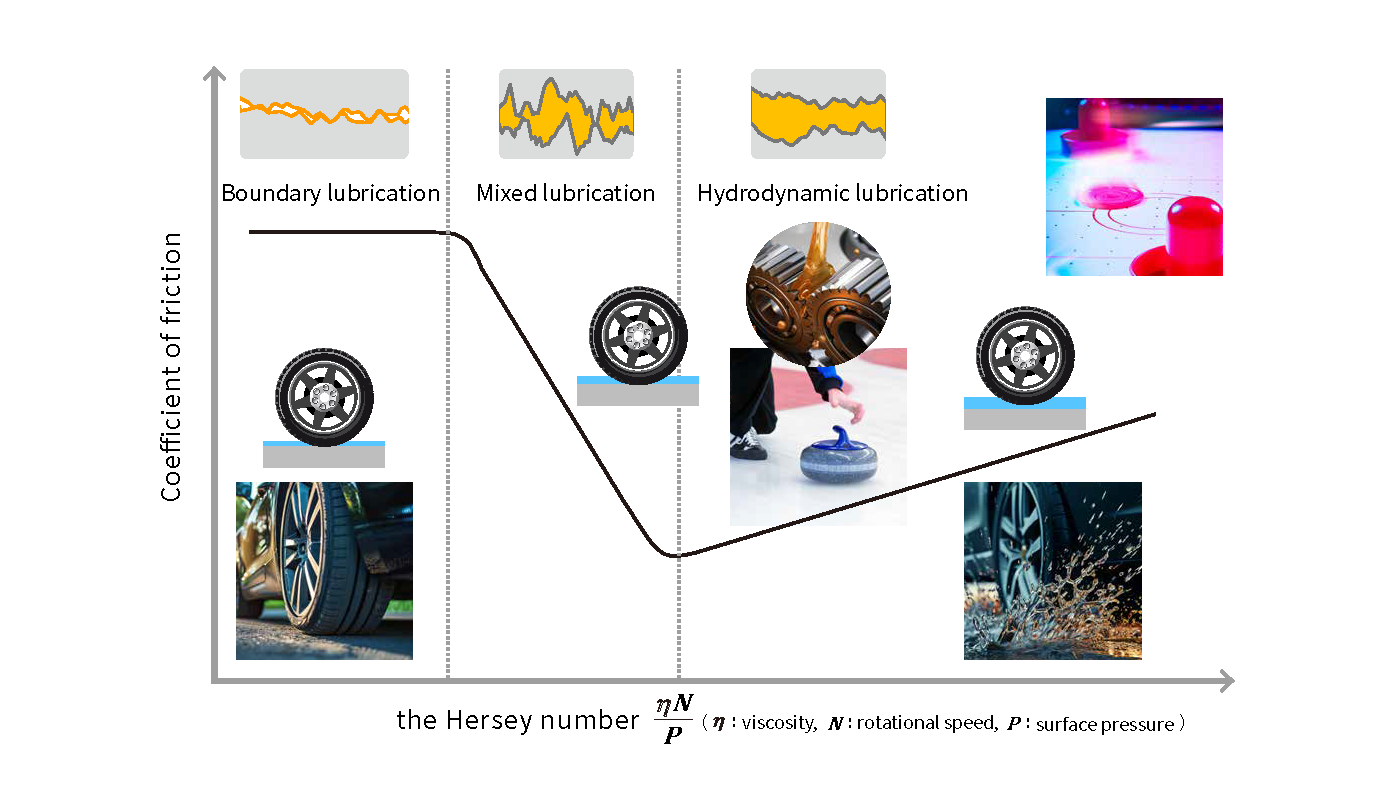

As introduced in Part 1 with the Stribeck curve, lubrication performance is typically characterized using factors such as the lubricant's viscosity, the relative speed between surfaces, and the applied pressure (see Figure 1). In the case of oil seals, for example, a very thin film forms between the shaft and seal surfaces when the shaft rotate. This is known as boundary lubrication, where direct surface contact dominates. As rotational speed (the relative velocity between surfaces) increases, a fluid film begins to form, shifting the system into mixed lubrication, and eventually into hydrodynamic lubrication. In the mixed lubrication region, the coefficient of friction decreases as speed increases. Once a complete fluid film separates the two surfaces, the coefficient of friction reaches its minimum. However, if the rotational speed continues to increase and the system enters the fluid lubrication region, the coefficient of friction begins to rise again gradually.

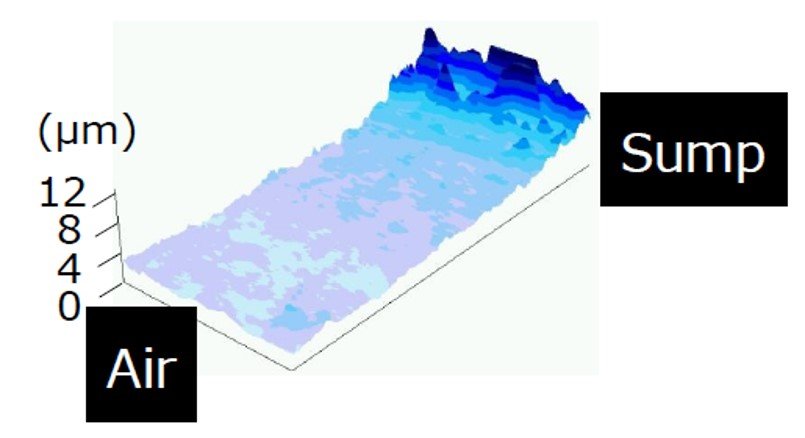

When the shaft rotates, the sliding surface of the oil seal generates a pumping effect that draws oil inward toward the oil side, forming a lubricant film. Interestingly, the thickness of this oil film isn't uniform — it varies depending on the location within the sliding surface. Closer to the oil side, the film is thick and forms a hydrodynamic lubrication state. However, the film becomes thinner toward the outer (air) side, resulting in a state closer to mixed lubrication (see Figure 2). At NOK, research is also underway to develop formulas that can model and calculate this variation in oil film thickness.

That said, this line of research is anything but easy. “There’s still so much we don’t understand in this field — even lubrication itself hasn’t been fully explained,” says Takao Horiuchi of the Tribology Research Section, Engineering Research Department. Despite that, NOK is “developing devices that visualize lubrication conditions in oil seals through a variety of methods,” he adds.

“Making the invisible visible”: Visualizing lubrication conditions from every angle

Since the 1960s, lubrication research has always involved attempts to visualize phenomena that can't be seen with the naked eye, such as what's happening on sliding surfaces. Various techniques have been employed, including photoelastic stress analysis, contact surface observation, Laser Induced Fluorescence, and optical interferometry.

Here, we’ll look at two recent visualization approaches: one focused on the boundary lubrication characteristics of rubber, and the other on visualizing grease lubarication film.

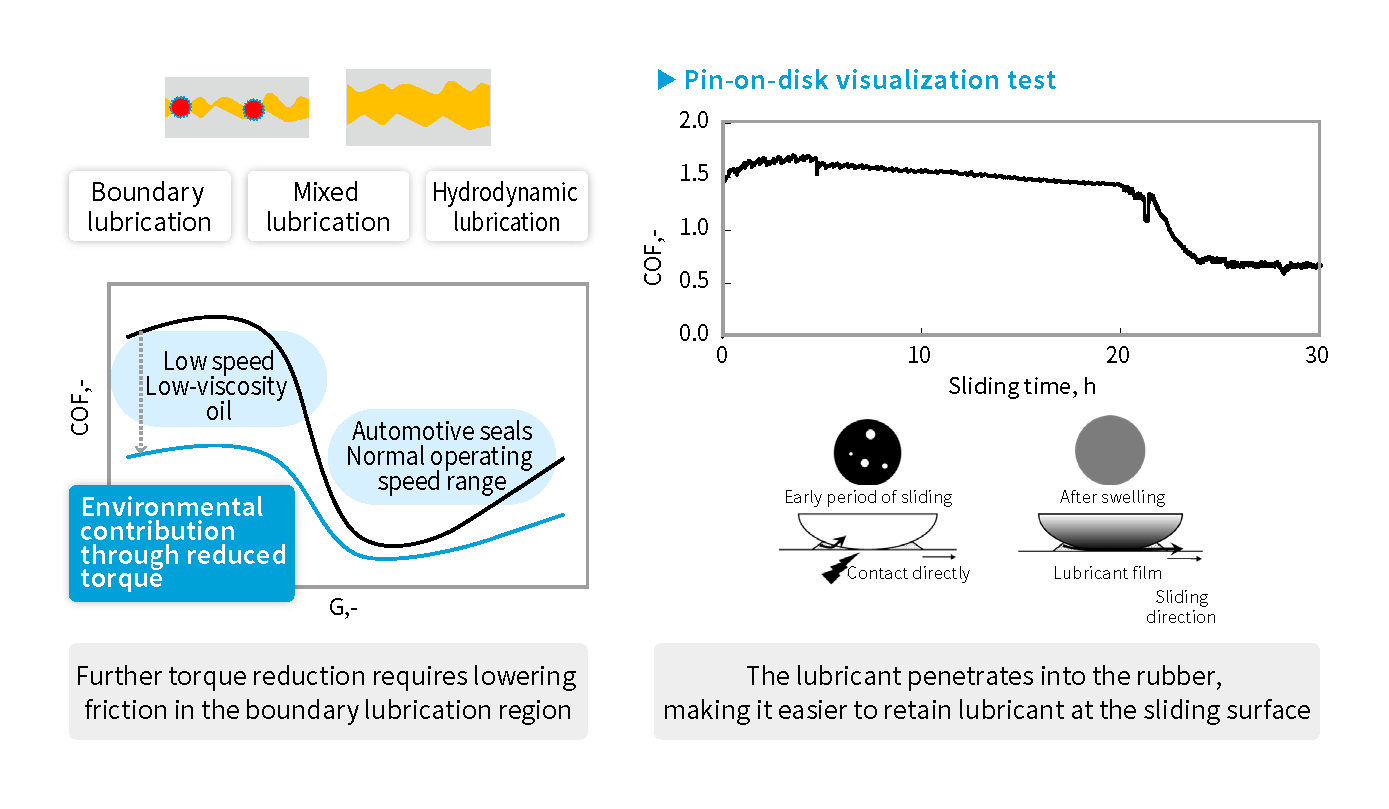

Research into the boundary lubrication characteristics of rubber

Unlike metal, rubber undergoes significant deformation when subjected to external force, and it can return to its original shape once that force is removed. Chemically, its molecular structure is similar to that of commonly used lubricating oils, so its compatibility with lubricants must be carefully considered. Because of these factors, many aspects of how boundary lubrication works in rubber remain poorly understood compared to metal. “Uncovering those mechanisms and understanding the underlying principles could be a major step toward improving the performance of oil seals,” says Horiuchi.

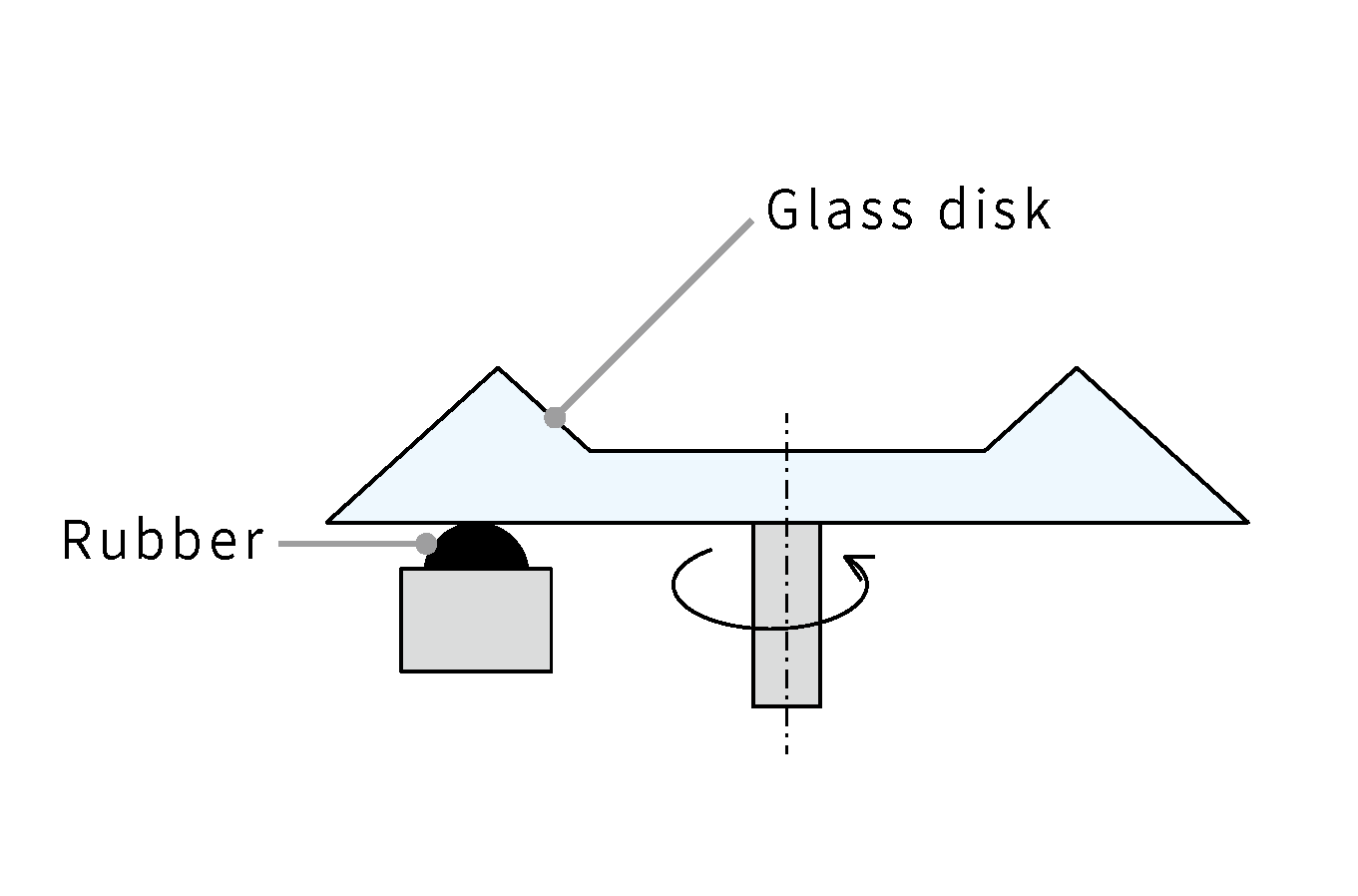

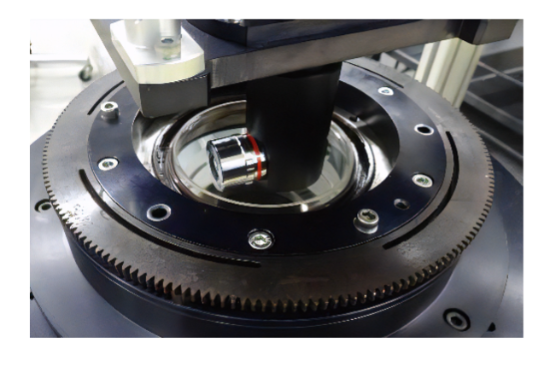

To explore this, NOK developed a pin-on-disk visualization test system (Figures 3 and 4) that allows for friction measurement and direct observation of the sliding surface. The setup enables researchers to observe how rubber behaves in contact under sliding conditions. A rubber pin is pressed against a glass disk, and the disk is rotated to generate friction, making it possible to observe changes in the rubber.

Because rubber has larger molecular gaps than metal, oil tends to be absorbed into those gaps; in effect, the rubber "soaks up" the lubricant. This helps the rubber retain lubricant more easily at the sliding interface. By visualizing these changes, the team aims to better understand how the lubrication state evolves over time.

Research into lubrication using grease

Lubrication with grease, a semi-solid substance that decreases in viscosity when in motion, remains poorly understood in many respects. For example, consider butter: at rest, it retains its shape, but apply a little force and it collapses. In that state, it can’t quite be called a fluid — but if you spread it very thinly or rub it quickly, its behavior becomes more fluid-like.

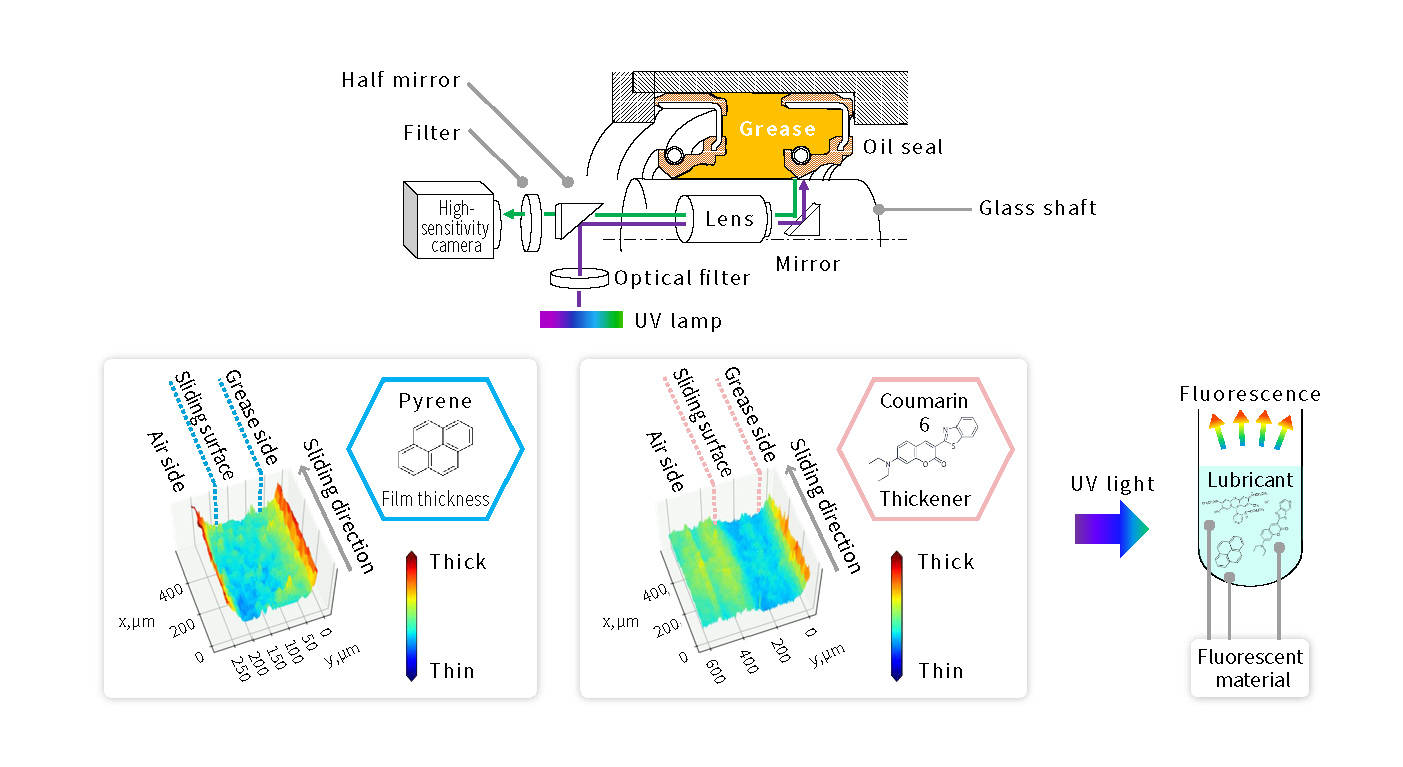

Grease is essentially oil thickened into a semi-solid form by adding a substance called a thickener. When grease is used in combination with a seal, understanding the lubrication state depends heavily on how this thickener behaves on the sliding surface. To investigate this, NOK is conducting research using a technique called fluorescence imaging, which allows the separation and observation of both the oil film and the thickener. Fluorescence imaging involves adding a fluorescent material that emits a different color when exposed to ultraviolet light, allowing researchers to measure its quantity and observe its behavior. In this case, a fluorescent substance is mixed into the grease, and UV light is applied during sliding to visualize the fluorescence. This approach makes it possible to observe how the grease film as a whole changes during motion, and how the thickener is distributed across the sliding surface. Additionally, by replacing a conventional metal shaft with a hollow glass shaft, researchers can observe the oil film thickness and thickener distribution from inside the shaft during operation of the oil seal (see Figures 5 and 6).

How can we maintain optimal lubrication? Can we develop a system where lubricant doesn’t run out?

At NOK, R&D into lubrication technologies continues through conventional approaches and entirely new concepts aimed at achieving lower friction. The concentrated polymer brush (CPB) and a novel self-lubricating rubber are two such approaches.

CPB is a surface treatment in which molecular chains are densely grafted onto materials such as metal or silicon, forming a brush-like layer at the microscopic level. Similar to how water stays trapped between the bristles of a toothbrush, this brush structure helps retain lubricant. Coating the surface of metals and other materials with CPB aims to sustain a hydrodynamic lubrication state. by keeping the lubricant in place. The self-lubricating rubber approach involves modifying the rubber compound itself to control the interface at a molecular level, enabling it to exhibit lubricating properties on its own.

In this way, tribology research at NOK has expanded beyond investigating the fundamental behaviors of friction and lubrication or developing visualization techniques. It now includes the creation of systems designed to actively and efficiently maintain ideal lubrication conditions. NOK’s challenge to "conquer" friction is far from over.