Friction: Mysterious yet Ever-Present — The Science of Tribology

Exploring lubrication research behind the oil seals that prevent rotating shaft oil leakage (Part 1)

Friction is something we rarely think about, yet it’s all around us. It’s what allows us to walk, wear clothes, and even why mountains can form (without friction, soil wouldn’t stay in place.) Because it’s such a constant part of everyday life, we often take it for granted.

But in manufacturing, especially when it comes to machinery, friction becomes a critical factor that can determine how well a machine performs. For a company like NOK, which develops a wide range of seal products, friction is a critical factor in mechanical performance, and exploring its mechanisms is key to advancing its technologies.

Tribology, the science of friction, lubrication, and wear, plays a vital role in maintaining the performance of operating machinery

Friction always occurs when parts come together in machines and tools, whether in motor shafts or engine pistons. Among the most common challenges in manufacturing is the friction generated by moving parts. When contact surfaces rub together over time, heat builds up and components begin to wear down. This can lead to reduced performance and even failure. The key is to reduce friction to allow parts to move reliably and consistently. Lubrication is one of the main ways to achieve that.

Tribology is the field of science that deals with friction, wear, lubrication, and related surface phenomena. The term comes from the Greek tribos (to rub) and -logy (study). According to Yohei Sakai from the Tribology Research Section in the Engineering Research Department, “The field began with troubleshooting issues caused by friction and wear. But today, the focus is shifting to controlling those effects in a way that suits each application.”

Even now, tribology remains relatively underdeveloped at the global level, Sakai explains. It draws on a wide range of disciplines: physics and chemistry on the natural science side, and materials, mechanical, and electrical engineering in applied research. Tribology related to rubber is especially under-researched, with many aspects still not fully understood. This article focuses on NOK’s work in tribology, particularly its research into friction and lubrication.

Lubricants such as oil are often added between contact points to reduce friction. However, because liquids tend to leak through gaps, it’s essential to prevent leakage and keep the oil level consistent for stable operation. This is the job of the oil seal. Oil seals are essential components used to seal machines in a wide variety of industries, from automobiles and aircraft to ships, trains, construction and agricultural machinery, petrochemical plants, and home appliances. At NOK, these products are manufactured based on a proprietary seal theory, ensuring high and consistent quality worldwide.

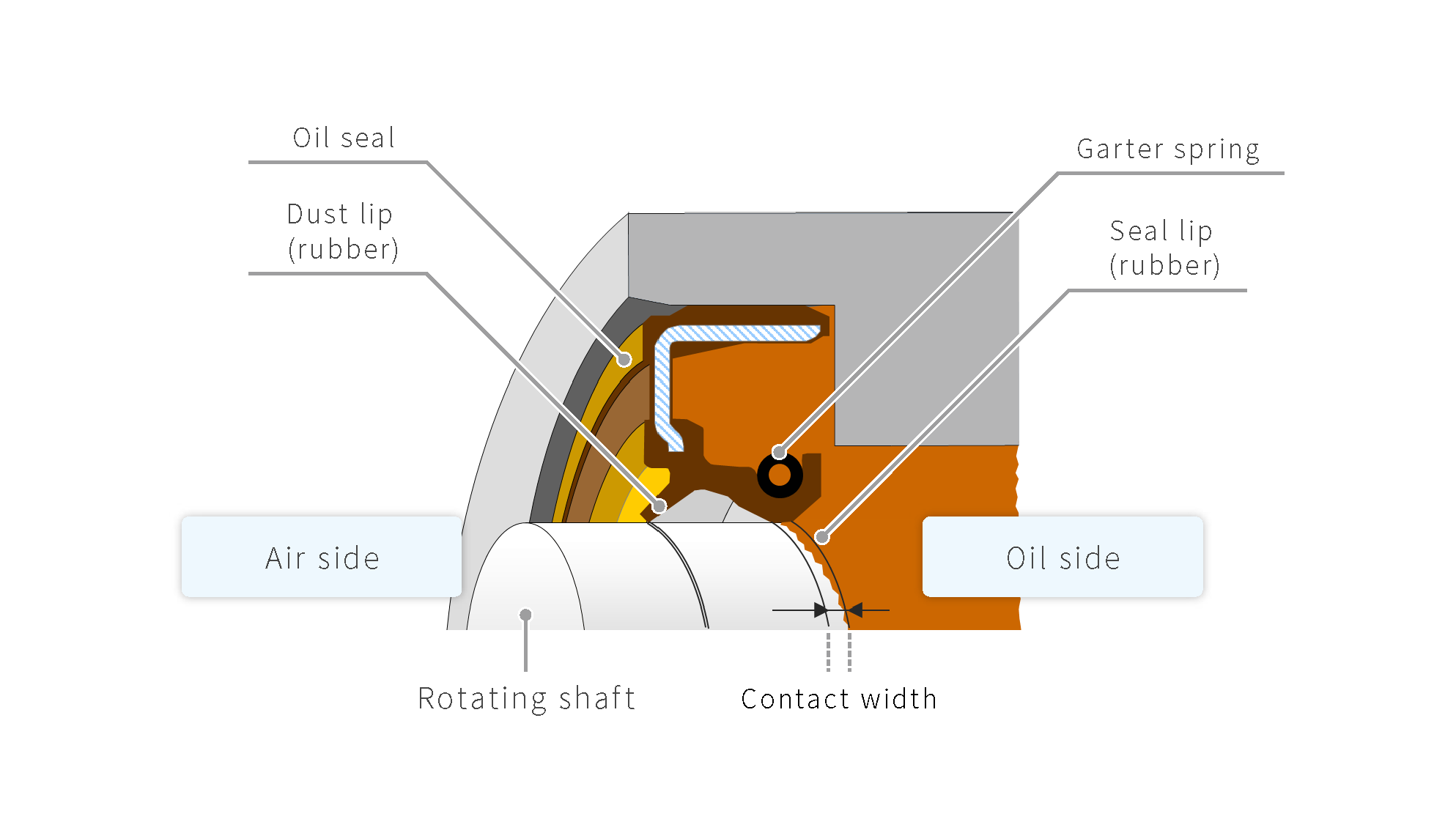

Let's take a look at how oil seals are structured. As the name suggests, they are used to seal in oil. A typical oil seal consists of a metal ring, synthetic rubber, and a garter spring that holds the seal tightly against the rotating shaft (see Fig. 1). The parts that slide against the shaft, the seal lip and the dust lip, are made of rubber. The tips of these lips press against the shaft surface, where the seal lip keeps oil from escaping, and the dust lip blocks external contaminants from entering.

When the lip comes into direct contact with the rotating shaft, the rubber surface wears down, causing oil to leak. To prevent this, a very thin oil film is maintained between the oil seal and the rotating shaft. This creates a state known as hydrodynamic lubrication (explained in more detail below), which helps reduce wear on the lip. In addition, the seal lip is designed so that the contact pressure is slightly biased toward the oil side. Combined with the micro-scale roughness of the lip surface, this creates a pumping effect that draws liquid inward, helping prevent oil from leaking to the outside. At NOK, research in tribology related to rubber materials is leading to the development of products like oil seals that maintain an optimal balance between sealing and lubrication.

Hydrodynamic lubrication: The mechanism supporting oil seal performance

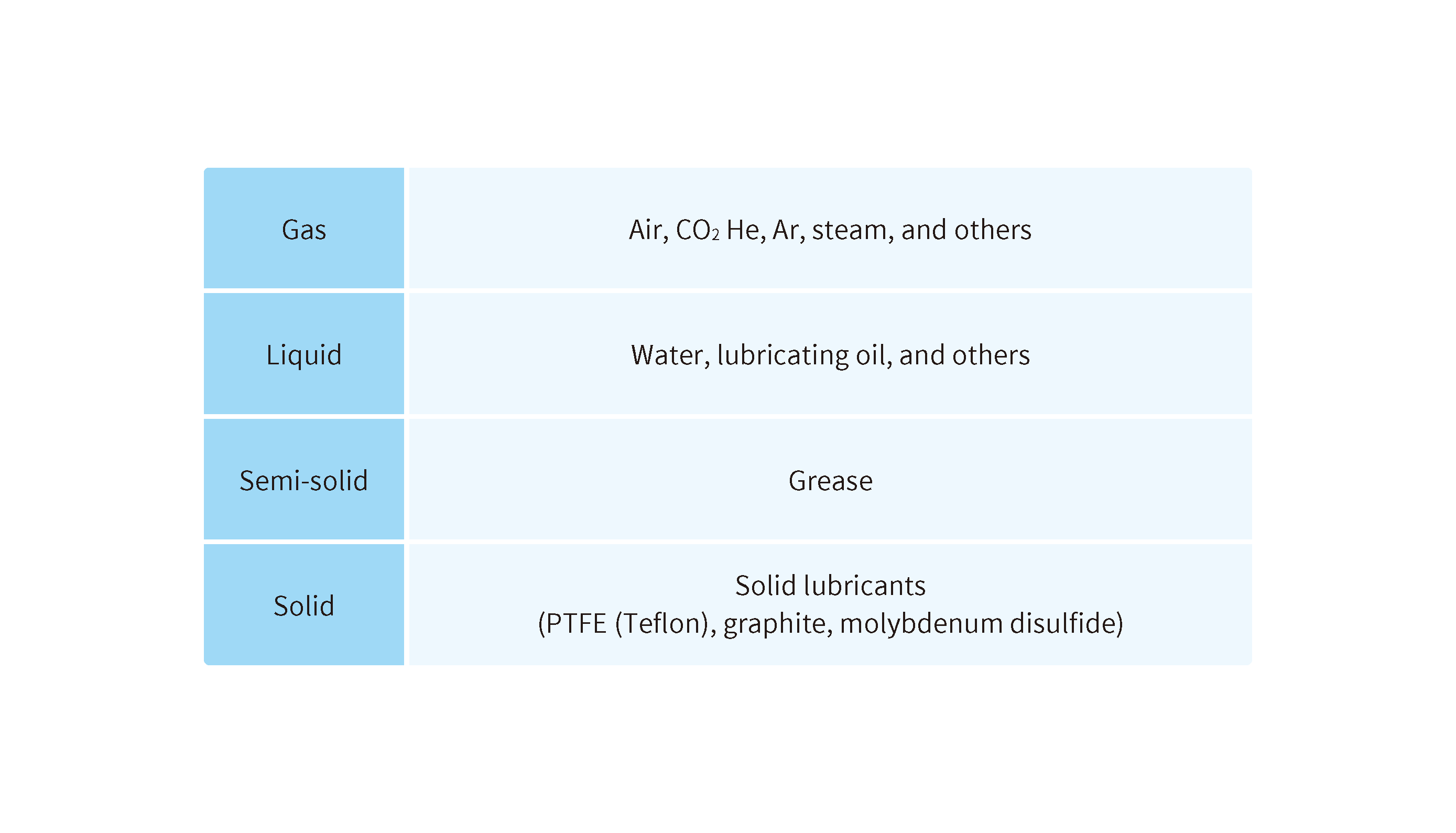

Lubrication works by inserting a lubricant between the sliding surfaces of two solids to form a film that separates them. This reduces both friction and wear. Lubricants can be gases (such as air or other types of gas), or liquids (such as water or lubricating oil), as shown in Figure 2. There are also semi-solid lubricants like grease, which typically behave like solids but deform when force is applied. In addition, fluoropolymer coating often used on frying pans, also act as solid lubricants. These coatings prevent sticking and improve surface glide, effectively serving a lubricating function.

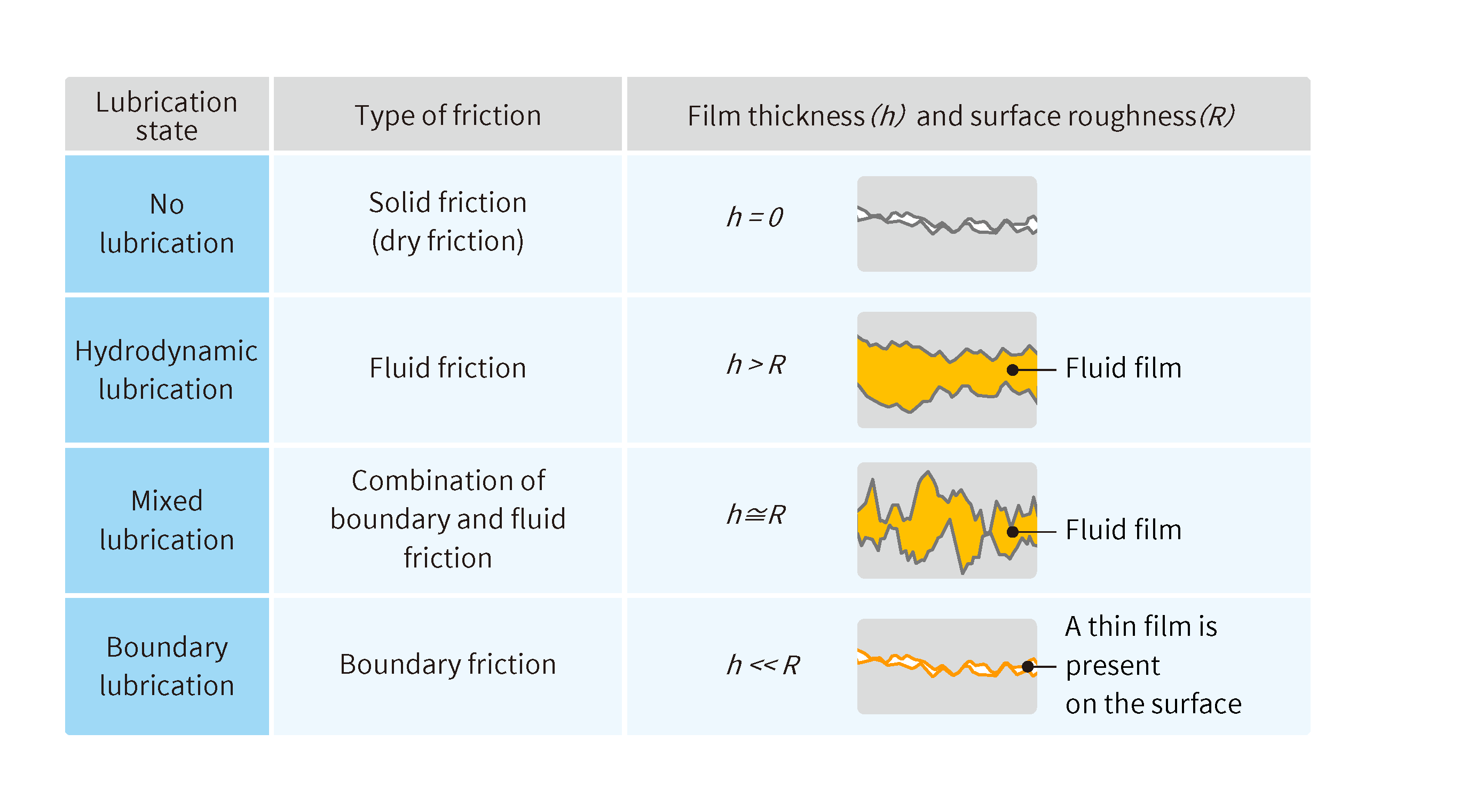

The term “lubrication” may sound simple, but in practice, it falls into three distinct categories depending on the condition of the contact surface.

-Hydrodynamic lubrication: A sufficient amount of lubricant forms a complete film between the two surfaces, preventing any direct contact.

-Mixed lubrication: The film becomes thinner, and some peaks of surface roughness come into contact.

-Boundary lubrication: Although a thin film is still present, most of the surface areas are in contact and rubbing against each other.

These are highlighted in Figure 3.

Each state involves a different degree of friction. The magnitude of friction depends on the actual contact area between two objects. Here, "contact area" refers not to what we see with the naked eye but to the microscopic surface area at the molecular level.

At first glance, fluid lubrication, where the lubricant film is thick enough to prevent contact between surfaces, might seem ideal. But that’s not necessarily the case. This is where things become complex, and where science plays a key role. In reality, the most desirable state is often somewhere right at the state between mixed and hydrodynamic lubrication.

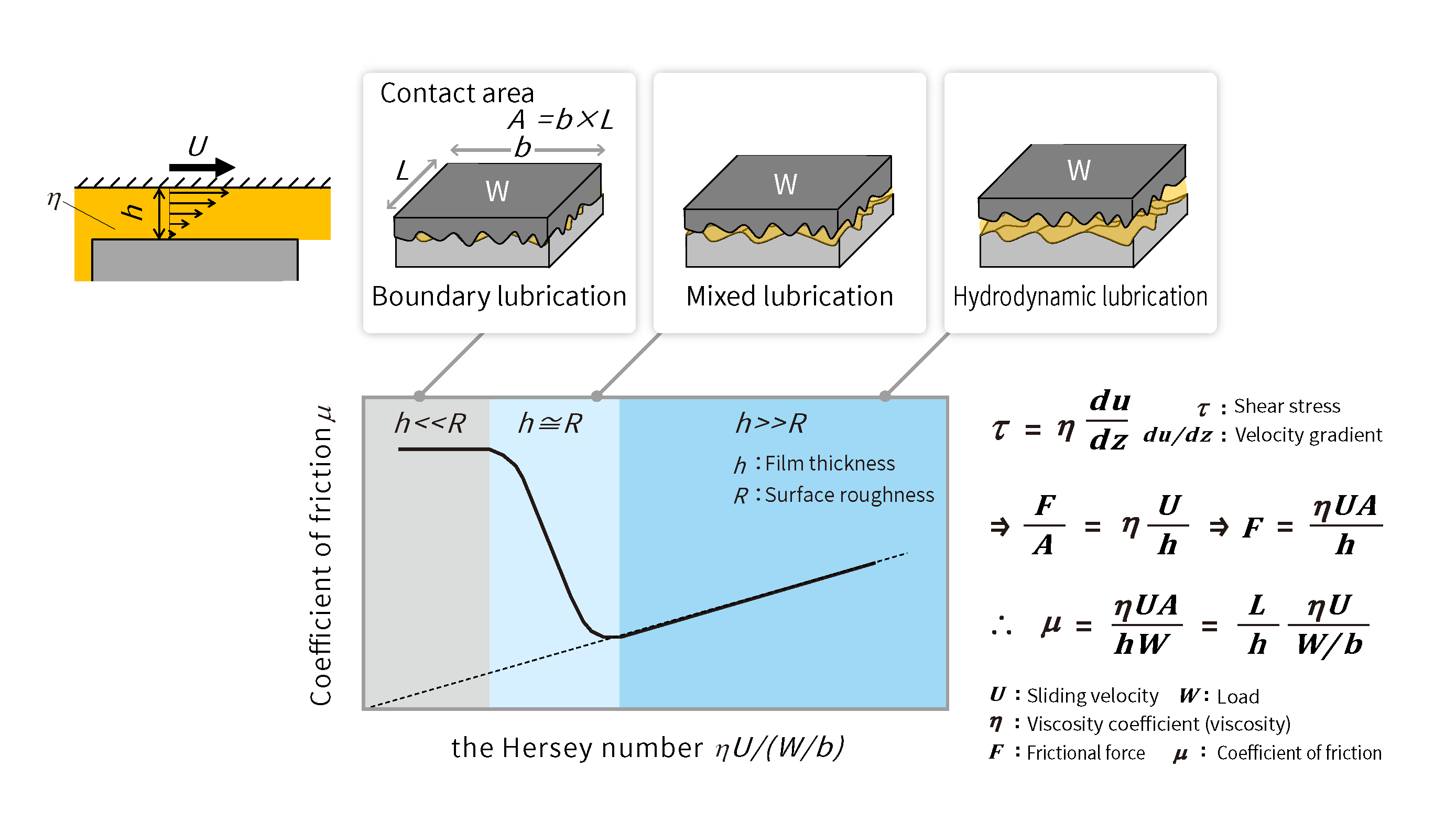

Formulas can help us scientifically understand the physical states involved in lubrication. The magnitude of friction between two objects depends on the mass of the material and the coefficient of friction between the two surfaces. When lubrication is involved, additional factors come into play, specifically, the viscosity (thickness) and the film thickness of the lubricant. The higher the viscosity, the higher the friction; the thinner the lubricant film, the higher the friction.

These relationships are illustrated in the Stribeck curve, which shows how different lubrication states behave under varying operating conditions (see Figure 4). The horizontal axis represents the Hersey number, which is a function of the relative speed of the moving objects, the load applied, and the properties of the fluid (the lubricant). The vertical axis shows the coefficient of friction. In the hydrodynamic lubrication region, the two surfaces are fully separated by a lubricant film, which keeps friction low. However, if the fluid's viscosity or sliding speed increases, friction also increases. On the other hand, when the fluid’s viscosity or speed decreases, the film becomes thinner. This leads to partial surface contact, transitioning the system into mixed lubrication, where friction rises. If the speed continues to drop or the fluid film disappears entirely, the two surfaces come into direct contact. This results in boundary lubrication, where the friction force stabilizes at a nearly constant level.

Even if a phenomenon can be explained scientifically — as with the Stribeck curve — it's not always clear whether the conditions assumed in theory truly match what's happening inside an actual component. That's why a deeper understanding of lubrication requires grasping what's occurring at the material level within real-world products. NOK's tribology research includes efforts to capture this reality through observation, measurement, and simulation. In the following article, we'll explore the challenges in uncovering this hidden physical behavior.