Stronger, Safer, More Sustainable: Engineering Expertise in Rubber Processing Unlocking the Source of NOK Group's Value: Rubber (Part 2)

When force is applied, rubber stretches and contracts, and when the force is removed, it returns to its original shape. Although it appears solid, it behaves closer to a liquid, making it a unique material. At NOK, we analyze its structure across a wide range of scales and are developing new technologies to deliver safer, more sustainable rubber products. We introduce our initiatives with a focus on crosslinking, the process essential to imparting these properties to rubber.

Crosslinking that gives rubber strength and durability

Rubber is formed from long, chain-like molecules (polymers) that are intricately linked. Before the vulcanization treatment — which imparts the elastic stretch and return to form we associate with rubber — the material has little elasticity and is clay-like. At the molecular level, the chains are only physically entangled, with no chemical bonds (crosslinks). It is like tangled yarn that unravels easily when pulled and does not return to its original shape.

During vulcanization, compounding agents are mixed into the polymer and the mixture is heated at high temperature. Chemical reactions then "bridge" the polymers to one another, restricting their movement. This is the crosslinked structure. The result is rubber that resists tension and pressure and withstands harsh conditions such as high temperatures and ultraviolet light.

Tackling degradation that unravels the crosslinked structure

Rubber's crosslinked structure degrades when exposed to heat, ultraviolet light, or chemicals. As crosslinks break, elasticity declines and the material hardens or cracks, which undermines performance and can lead to equipment failure or downtime. Because rubber is used in critical mobility and industrial components, understanding degradation is essential. At NOK, we use nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), based on the same principle as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), to visualize molecular structure. This lets us assess crosslink density and molecular mobility and clarify the mechanisms of degradation.

We also conduct analyses focused on chemical reactions. A familiar example is a concert glow stick used at live events: bending it before use breaks the inner ampoule, two liquids mix, a reaction occurs, and light is emitted. By observing this light, known as chemiluminescence, we can gauge how far the reaction has progressed.

NOK applies this principle to rubber. As rubber degrades, it emits a faint light that is invisible to the naked eye. Measuring this chemiluminescence makes it easier to detect degradation caused by changes in the crosslinked structure and to confirm the effectiveness of preventive measures.

Contributing to a sustainable society with "non-crosslinking rubber"

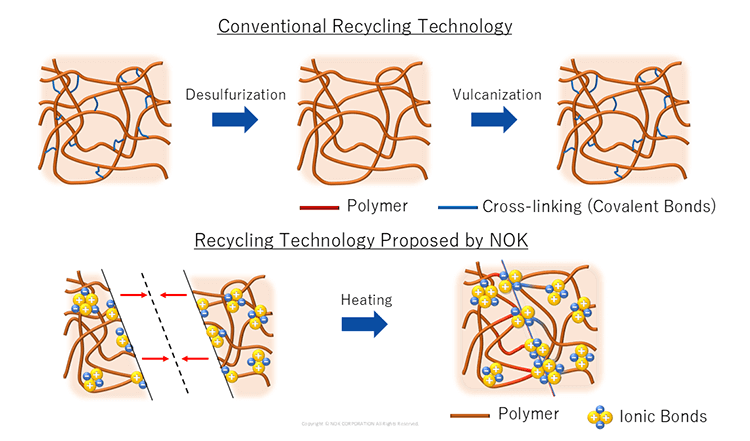

The crosslinked structure is key to rubber's performance, but it becomes a bottleneck when recycling older products. Desulfurization (removal of sulfur) is required to break those crosslinks, followed by re-vulcanization (forming new crosslinks by heating the rubber with curing agents under pressure) to suit the next application.

In recent years, as we work toward a more sustainable society, there has been a growing demand for manufacturing that facilitates resource recovery. In response, NOK developed the next-generation rubber "Links Rubber."

It replaces conventional crosslinks with ionic bonds. Because cations and anions attract electrostatically, the polymer chains bind to each other and can re-bond under pressure if there are small cuts or gaps, providing self-healing behavior. This makes it easier to re-mold and reuse aged rubber products and supports a circular economy in industry.

画面を拡大してご覧下さい。

To master rubber’s complex properties, we examine its internal structure from multiple perspectives and develop new technologies to meet evolving requirements. This continuous effort underpins the reliability of NOK's manufacturing.